An art that does not challenge itself is not art. As for filmmaking, more than a genre, the documentary is an attitude towards reality, therefore, it is the best approach when it comes the time to ponder about the possibilities and limitations of filmmaking as an art.

Guidedoc has chosen for you five memorable documentaries that celebrate the existence of cinema.

In case you didn't now, GuideDoc is a global curated documentary streaming platform. Watch the world's best award-winning docs from around the world. We have new movies every day.

5 — The Wonderful Horrible Life of Leni Riefesntahl by Ray Muller

Leni Riefenstahl became the world’s most famous filmmaker after providing Adolf Hitler´s regime with her prodigious filmmaking skills. In 1993, when she was ninety years old, Riefenstahl decided to commission the production of a documentary about her life. Eighteen directors refused to take the reins of the film for fear of being associated with the Nazi regime until German filmmaker Ray Muller accepted the challenge to make a bold portrait of the most controversial woman in filmmaking history.

In the documentary The Wonderful Horrible Life of Leni Riefesntahl, Riefenstahl talks to the camera and responds to Muller’s careful questions during the shooting. The film reviews the artistic life of the German filmmaker from her beginning as an actress of the melodramas directed by Arnold Fanck, her work as director of her first feature films at the dawn of sound cinema, to her golden years as the favorite filmmaker of the Nazi regime making films like The Triumph of Will, the majestic film about the Nazi convention in 1934.

Some scenes are remarkable, like the tense moments in which Riefenstahl discusses fiercely with Muller as he question her about the authorship and function that the Nazis made of her works, or the contradictions between her and the testimonies that Joseph Goebbels wrote about her in his autobiography, a scene in which Riefenstahl leaves the film set with indignation.

4 — Train of shadows by José Luis Guerín

The outstanding Spanish filmmaker José Luis Guerín finds an old collection of amateur films from 1930 and obtains the matter to investigate the possibilities of cinema to sculpt time and memory. The films were made by Gerar Fleury, a family father fond of cinema, who would shoot from time to time family films in the garden of his “chateau” in the French countryside. His children, his wife, the servitude and even himself appear on the screen in the grainy black-and-white image of a 16-millimeter movie while cycling, dancing or eating surrounded by nature.

In search of the stories hidden behind those characters that only live in a film frame, Guerin’s hand stops, rewinds and peeks a magnifying glass at the film, of which there is really no true trace. What we have seen so far has been only the reconstruction of a film of the past that the author has just imagined. When Guerin falls in love with the face of Fleury’s beautiful daughter, the director observes the frames in detail and then he films the shadows and relics that still remain in the chateau in present time. There, he also films a reenactment of those family scenes now in color 35-milimeter film. It is precisely this ambiguous dimension between truth and lies, the past and the unknown time, where Train of Shadows triumphs to perceive reality as a fascinating experience.

3 — Room 237 by Rodney Ascher

Room 237 was released in the Directors´s Fortnight section of the Cannes Film Festival, this documentary presents an outstanding voyage to Stanley Kubrick´s The Shining proposing a series of theories about hidden meanings and interpretations never before contemplated on the film. In front of our eyes, the scenes of The Shining illustrate the testimonies off-camera of different interviewees who give their appreciations of alleged subliminal messages or incredible coincidences of the elements on screen with historical events and symbolic conventions of humanity.

Among these considerations are the mentions to the elements that make allusions to the Nazi holocaust, the impossible dimensions of the architecture of the hotel in which the story occurs or the references to the myth of the Minotaur in elements of the props and when Jack Nicolson acts as a bull. The title of the film refers to the relationship between the room 237 of the hotel and the bedroom that appears at the end of another famous Kubrick film 2001: A Space Odyssey. Other assertions include that the film can also be seen in reverse to find another meaning to the story and clues to a possible allusion to Kubrick’s participation in the filmmaking of a fake Moon landing.

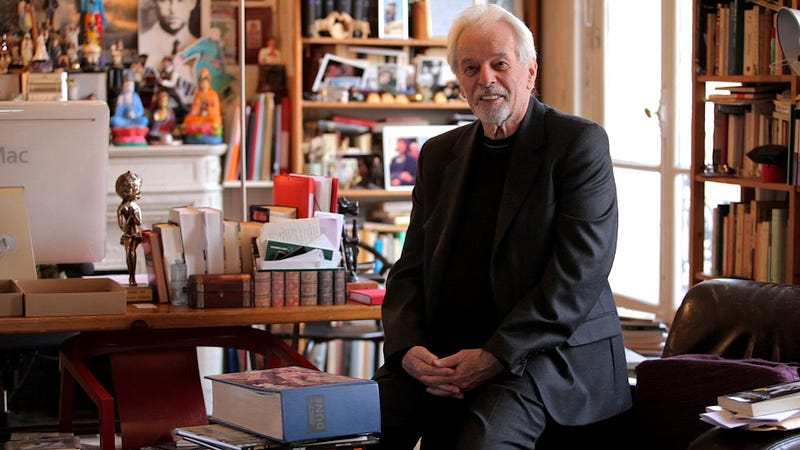

2 — Jodorowsky’s Dune by Frank Pavich

The eccentric filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky decides to tell the details of the biggest project of his life. Jodorowsky’s Dune is the film adaptation of the science fiction novel “Dune” written by Frank Herbert. After the success of his grandiloquent surrealist films, Jodorowsky received a budget of almost 10 million dollars for the production, from which he wrote an extensive script that had the volume of a phone book. To accomplish his ambitious project, he managed to gather a team of artists such as Pink Floyd for the soundtrack, Jean Giroud for the art department, and Orson Welles, Salvador Dali and Mick Jagger for the performances.

After spending two million dollars only on the pre-production stage of the film, the project lost viability and Jodorowsky lost the rights to make the film. In this documentary, Jodorowsky himself tell us about the anecdotes of the preparations for the shooting, the authorial vision of his imagined film and how the plans and sketches of “Dune” ended up influencing the imaginary of films like Star Wars, Alien and Terminator.

1 — This Is Not a Movie by Jafar Panahi.

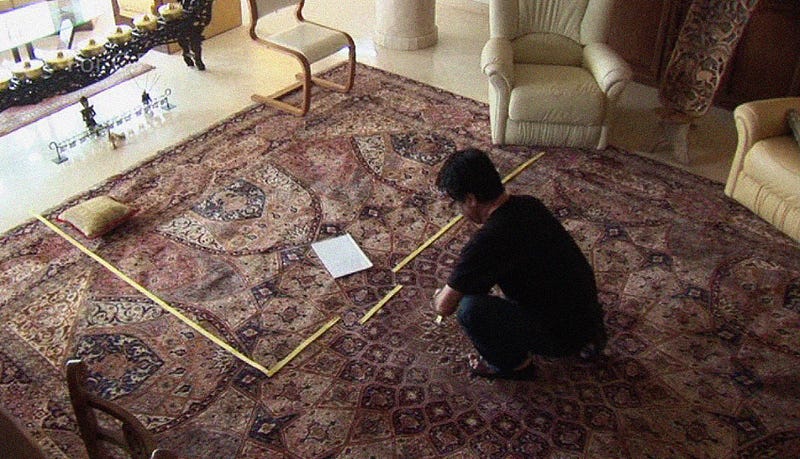

In 2010 the laureate Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi was sentenced to six years of house arrest and was banned from making films for the next twenty years. The unprecedented sentence was the reaction of the Iranian State to the critical content of his films, which questioned the status quo of the Persian country. But this was not enough for Panahi to desist from directing. Using his own cell phone and a small video camera operated by one of his friends, the Iranian filmmaker films himself in the closure of his apartment while waiting for the result of the appeal to his sentence.

In a claustrophobic approach, Panahi films his digression through the domestic corners, trying to give shape to his own impotence of not being able to make the art that gives meaning to his life. During the film he explain to us the intentions behind several scenes of his previous films, we see him talking on the telephone with his lawyer or making a simulation of one of the scenes of a film he can just imagine and might never become real. The film arrived at Cannes on a flashdrive that managed to get out of Iran hidden in a cake. Its premiere was the triumph of cinema over the censorship, an artistic lesson about giving image to prohibition.

Watch essential documentaries now on Guidedoc.